Words by Matt Pietrek

When we think about rum, the Caribbean is usually top of mind. But London also played an outsized role in rum history. The city was arguably the rum hub of the world for over a century, and the rum trade significantly changed London’s geography. It also contributed to two of London’s biggest disasters of the 20th century (but who could stay angry at rum, am I right? – Ed).

IN THE BEGINNING

While it’s well-accepted that rum was first made in the Caribbean around 1640, most of what was produced at that time was consumed locally or sent to nearby colonies. In those days it was Britain’s lust for sugar, rather than rum, that fuelled its Caribbean ambitions. Countless sugar-filled ships travelled to Bristol, Plymouth, Liverpool, and London, but very little rum made the same journey early on. Instead, British denizens enjoyed the “foreign brandy” and wines of France and Spain.

It wasn’t until the early 1700s that Caribbean rum started regularly flowing to Great Britain. The quantity was modest at first but quickly increased. In 1793, over two million gallons of rum flowed into London; the overwhelming majority of which was of Jamaican origin. Much of the imported rum went into punch bowls flavoured with spices from the empire’s far-flung holdings.

The astronomical amount of sugar and rum arriving in London created substantial fortunes for the merchant planter class, including George Hibbert, Robert Milligan, Thomas Plummer, and John Wedderburn (Yes, that Plummer and Wedderburn). Their trading houses occupied the streets near the Tower of London — Fenchurch Street, Mark Lane, Mincing Lane, and Fen Court among them.

With great West Indies wealth came great problems. The flotilla of cargo-stuffed ships had no place to unload upon arrival— all available docks along the Thames were occupied unloading previously arrived ships. Mudlarks, river pirates, and other ne’er do wells plundered cargo from the traffic jam of ships idling in the Thames awaiting dock space. The merchants mourned their losses, and the government fretted over the lost tax revenue. Something had to be done.

THE WEST INDIA DOCKS

Following years of vigorous debate, the solution agreed upon was an expansive complex of quays carved from the earth of the Isle of Dogs, a peninsula creating an enormous ‘U’ in the Thames. Several massive trenches were excavated between 1800 and 1802, including one stretching nearly a mile across the entire peninsula.

Surrounded by high walls, arriving ships were handed off to skilled dock employees who unloaded the cargo, then refilled the ships with export goods before sending them back into the Thames. Enormous, multi-story brick warehouses lining the quays served as bonded warehouses for dutiable goods, including sugar, tea and rum. Arriving ships could be unloaded, refilled, and back underway within days rather than months.

Comprised primarily of wealthy sugar and rum merchants, The West India Dock Company paid for the project’s construction. In exchange, the company had a 23-year monopoly on all incoming ship traffic from the West Indies. The cargo unloading and storage fees paid by ships using the docks created a healthy return for the dock company. The West India Dock’s business model was replicated shortly thereafter, creating the East India Docks for traffic arriving from the East Indies.

RUM QUAY

A special area of the West India Docks was known as Rum Quay and devoted exclusively to the rum trade. Between the warehouses and their cavernous cellars, Rum Quay could store 40,000 puncheons of 80% ABV rum at any moment. In today’s units, the equivalent of 57 million 70cl bottles at 40% ABV. Most of the rum slumbering therein was from Jamaica and Demerara.

Merchants who stored their casks at Rum Quay didn’t pay excise taxes until the casks were removed, so merchants had an incentive to leave the rum there until needed, often for many years. Among the merchants storing casks at Rum Quay were Lehman (“Lemon”) Hart, Alfred Lamb, and Thomas Lowndes, all names still used in today’s rum trade. The rum aged at Rum Quay constitutes the proper definition of “London dock rum.”

Roving bands of coopers monitored and repaired casks because the dock company was responsible for any losses beyond the expected angel’s share. No flames were permitted in the pitch-black, alcohol-rich air of the cellars, so coopers used pieces of tin attached to a stick to reflect sunlight directed to the cellar by a mirrored tube reaching up to the roof.

THE ROYAL NAVY AND DEPTFORD

While Rum Quay alone warrants a headlining role for London in the annals of rum history, the Royal Navy victualling yard at Deptford further cemented London’s importance. A mile downriver from the West India Docks, the Royal Navy’s vats blended much of the rum provisioned to navy ships. One of the navy’s vats held over 32,000 gallons! Much of the rum dumped into the navy’s Deptford vats came from the West India docks.

Among the best stories of Royal Navy rum is that of a dog presumed to have fallen into a vat and drowned. When the vat was later emptied, no dog was to be found. Instead, the bottom held many glass bottles with long pieces of string tied around their neck. We’ll let the reader guess why.

UP IN FLAMES

Disaster struck in 1933 when a fire destroyed Rum Quay and its millions of gallons of overproof rum. A newspaper headline proclaimed, “80-Feet Flames Seen 20 Miles Away.” The warehouses were subsequently rebuilt and restocked in time for the 1940 German blitz of London, when all the rum went up in flames again.

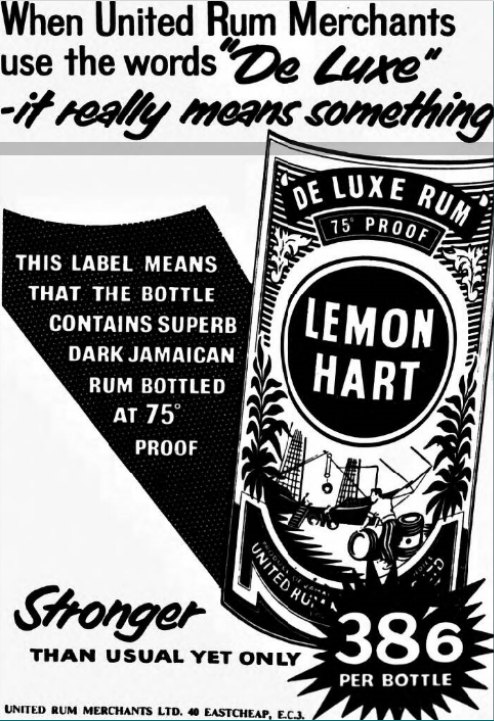

Many London rum merchants saw their facilities destroyed during the war, driving several to merge circa 1947 to form United Rum Merchants. The company’s powerhouse portfolio included Lamb’s Navy Rum, Lemon Hart, Red Heart, and Light Heart rums before they were scattered to the winds decades later.

As for the West India Docks and Rum Quay, container-based shipping that started in the 1950s rendered London’s 1800s-era docks obsolete. The Canary Wharf redevelopment of the 1990s replaced the warehouses with skyscrapers; One Canada Square now rises over the site of Rum Quay, the former epicentre of British rum.

You can read more of Matt’s rum writings on his website, the indispensable RumWonk.com and in his latest book Modern Caribbean Rum