Rum can be a tricky subject to approach – how do you define it, what does it taste like, and how do you have a clue what you are buying? Unlike many whiskies where there are laws governing production which guide you as to their style – for example single malt or bourbon – in most instances rum lacks both clearly-defined laws and style descriptors. Instead, we most commonly see descriptions like ‘white’, ‘gold’ and ‘dark’ on the label, but what does this exactly tell you about the rum? The answer – not a damn thing.

The current labels and what they mean – or don’t

White Rum

It would be easy to believe that rums which are clear in colour are all unaged and similar in flavour – but do Bacardi and Wray and Nephew taste the same? Describing a rum as white is not an indication of flavour or of age, nor even of colour if we are being very technical. A clear rum could indeed be unaged but equally, such as in the case of Cuban rums, they might be aged for a period and then have their colour removed by charcoal filtration. Similarly, you can have a molasses-based white rum that is light in flavour or a big, grassy flavourful sugarcane juice rum that is the exact same colour.

Gold Rum

Does this term indicate that the rum has been aged, and if so for how long? In this group you can find a rum like Angostura 5 Year Old – easy-drinking and great for cocktails – shoulder-to-shoulder with Caroni, which is big and powerful with so much flavour it almost hurts. How can these two sit in the same broad category?

Dark Rum

Well, this is the worst offender of all. Many people would think that the colour means it has been aged. but a lot of ‘dark’ rums just have caramel added to them for colour and haven’t even sniffed a barrel.

Clarity Not Colour

So how do we decipher rum? We could talk about the colonising country and the associated styles – French, English, Spanish – but again within these categories there is so much variation. If you take English rums, for example, it would mean that rums from Jamaica and Barbados would sit in the same camp – if you know your rums you’ll know that the bold tropical notes of Jamaican rum have no similarity to the rich fruity, spicy notes in the rums of Barbados.

Instead, we need to consider what actually influences flavour. The base ingredient is a great place to start, and should have the main influence on the final product. In whisky corn gives sweetness, grain a roundness and softness on the mid palate, and rye a spiciness on the finish. In rum, too, the ingredient is the basis of all flavour and this is where any classification should begin.

Sugarcane Juice

Rums made from freshly pressed sugarcane have an amazing grassy, vegetal note and an inherent freshness to them, whether aged or not. When they are aged they take on a notes of sesame seed, linseed oil and a nutty character on the finish.

Molasses

Rums made from molasses tend to carry less flavour from the base product over and are more affected by distillation, so they can be anything from packed with notes of brown sugar and rich fruit to light and easy drinking. They will, however, always feature the sweetness and soft vanilla flavours from the base product.

There is a third category which is sugarcane syrup which gives styles similar to molasses. You can find more details on what the three base ingredients are on The Whisky Exchange Focus on Rum page.

Whilst the yeast used to ferment the base ingredient can also have a massive influence on the end product, this level of detail would over-complicate matters in any classficiation. The next key step for us is distillation. Just as in Scotch whisky production, the type of still is used will have an effect – a continuous still will produce a lighter distillate than a single batch pot still.

Our New Classification

Seeking to highlight the importance of the base ingredients in the final rum as well as the production method, we took the classification designed by Luca Gargano and Richard Seale – the Gargano Classification – and put a Scotch spin on it. In the same way that we talk about ‘single’ malt, we now talk about ‘single’ to indicate rum from one distillery, and ‘blended’ to denote that from two or more distilleries.

Alongside our new formal classification we also went one step further and split the rums into flavour camps, allowing those unfamiliar with distillation and what it gives to the spirit to further navigate the category.

The Single Distillery Rums

Single Traditional Pot Still – these are rums made in a pot still that tend to be fuller bodied and heavier in style, with plenty of flavour. Most Jamaican rums fall into this category. We found that these rums fall into either the Tropical and Fruity or Rich and Fruity flavour camps.

Single Traditional Column Still – these are made on a simple column still (like a Coffey still) that produces rums with plenty of flavour but without the weight and power that comes from the pot still. These tended to come under the Rich and Fruity flavour camp and, if from sugarcane juice, Herbaceous and Grassy. Rums from Martinique mainly come into this category.

Single Traditional Blended – these are rums made from a blend of distillate from a pot still and a simple column still. Barbados is a classic example of this style. These rums have the weight of the pot still, but are not too heavy and have some lighter notes from the column. These are often in the Rich and Fruity camp.

Single Modernist – these are rums that contain any influence from large multi-column stills that have a purifier on them. This means the spirit that comes out is mainly light and fairly neutral in style. Plenty of rums that are produced for mixing from places like Puerto Rico and Cuba are made in this way. Also those aged ones where wood is the desired dominant flavour. These rums may also have pot or column still distillate in them, but that large still will always influence the final spirit. Modernist rums mainly sit in the Light and Uncomplicated camp, or the Dry and Spicy camp where wood is the principal flavour influence.

The Multi-Distillery Rums

The distillation styles and flavours above also feed into those brands that blend between distilleries. These for the sake of simplicity we split into two categories:

Blended Traditionalist – those blending between distilleries on pot or traditional column stills or a combination of both, for example the Duppy’s Share (a blend of rums from Barbados and Jamaica from both pot and traditional column stills).

Blended Modernist – those that blend between distilleries with a large multicolumn influence somewhere in the blend, for example Pussers Navy rum.

Final Flavour Factors

While the classification allows us to decipher much about what’s in the bottle, there are a couple of other factors that affect flavour in rum, which we have highlighted in each product description to give you even more information about flavour. One of these is whether sugar has been added after distillation to give sweetness to the spirit. When a high percentage of sugar is added, these rums tend to sit in the Rich and Treacly category.

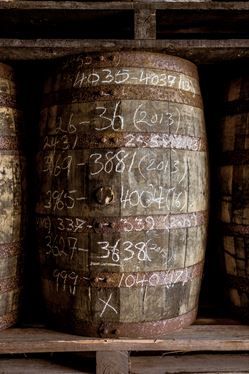

The second important post-distillation influence is where the spirit was aged. In Europe we know the angels share is 1-3% and the influence of the oak can take a long time to really marry with the spirit. In hot climates like the Caribbean, however, this angels share can be between 8-13% and the influence of the oak on the spirit tends to be more rapid. Whether the rum is aged at origin is therefore also important in the final flavour of the rum.

How we group and describe all these key influences on the final spirit we hope, start to give you a better guide as to the character of the rum in the bottle. Whilst we know it is probably not perfect, we believe it is a step in the right direction in allowing you to have the confidence to delve deeper into this beautiful category.